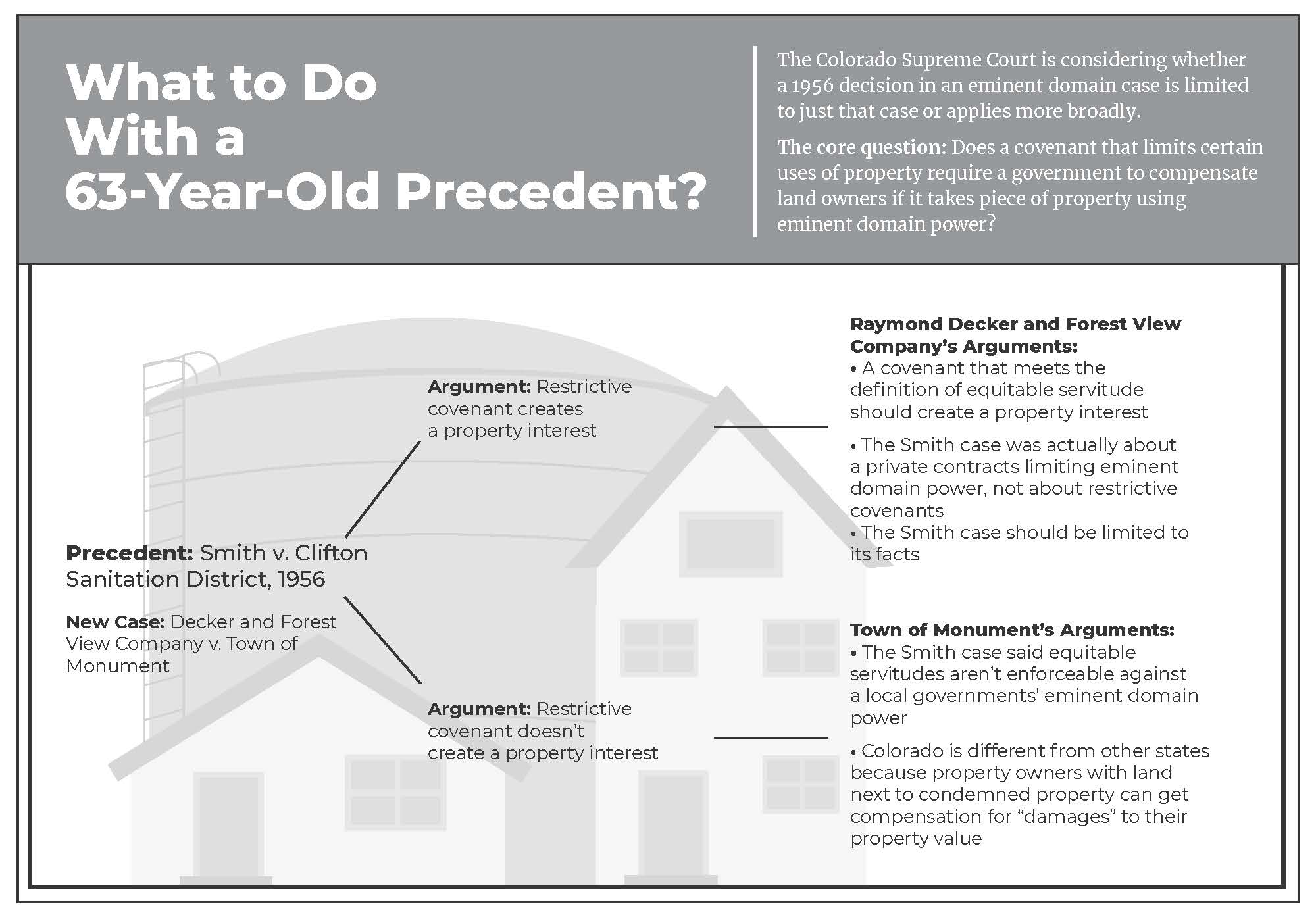

The Colorado Surpeme Court heard oral arguments Tuesday in an eminent domain case that asks whether a restrictive covenant creates a property interest that landowners can get compensation for if a local government uses its eminent domain authority against the covenant. The answer depends on whether a 63-year-old precedent made a broad rule of law or a limited one based on an odd set of facts.

This case involves a parcel of property the Town of Monument bought in a residential neighborhood to build a water storage tank. The town filed suit to use its eminent domain authority to get around a covenant that prohibits such structures, which applies to all lots in the subdivision.

But some property owners who intervened in the case claimed Monument would have to pay each of them for the loss in their property’s value because the covenant benefitted all property in the subdivision. In addition, the State Board of Land Commissioners — which is no longer a party in the case — claimed Monument’s property lot couldn’t be exempted from the restrictive covenant because it is a compensable property interest.

The 1956 case Smith v. Clifton Sanitation District involved a restrictive covenant clearly imposed by property owners to block a public entity’s acquisition of property for a public purpose, and the Colorado Supreme Court ruled the covenant was not a compensable property interest.

In the case, property owners enacted a restrictive covenant barring the use of their land as sanitation disposal after negotiations with a sanitation district to buy property for that purpose fell apart.

But the Court of Appeals found the Smith ruling reached beyond that type of situation. That court’s decision overturned the district court’s ruling that the covenant is a compensable interest. The Court of Appeals acknowledged the fact pattern in Smith is unusual but noted the Supreme Court’s decision didn’t depend on the property owners’ intent when it enacted the restrictive covenant.

Richard Hanes, representing petitioners Forest View Company and Raymond Decker, laid out his arguments: A restrictive covenant that meets the definition of equitable servitude should be a property interest entitled to compensation.

Broadly, equitable servitude is an agreement between parties that limits their use of property. It benefits and burdens the original parties as well as their predecessors and future owners.

Addressing the Smith precedent, Hanes said that case addressed a private contract restricting eminent domain powers rather than whether a restrictive covenant is a property interest. And the decision was limited to its facts, he said.

Justice Richard Gabriel asked Hanes about the possibility of eminent domain’s cost getting prohibitively expensive for a local government if a restrictive covenant is a property interest, which he said would suggest “impairment” of eminent domain.

“The fact is that the Constitution is there, and whether it’s a small bite on the public or a large one doesn’t affect the takings clause of the Constitution,” Hanes answered. He said he believes the Court of Appeals misinterpreted the Smith case by applying it to the question of restrictive covenants creating property interest.

“[The Smith court] decided on the basis that it was a private contract and that private contracts cannot influence the government’s right of eminent domain,” he said. “They can’t reject that.”

Justice Melissa Hart said she agreed with Hanes’ interpretation of the Smith case. She asked him why the restrictive covenant in this case wouldn’t also be considered a private contract that can’t limit eminent domain authority.

“It’s not a contract in a sense that it was signed by the parties that are bound by it and are burdened by it,” Hanes answered. “It was developed by the scheme of the development of the subdivision, Forest View Estates, and it fits the elements of an equitable servitude.”

Hanes said he believes whether the restrictive covenant fits the criteria for equitable servitude should determine whether it is a property interest, and he said the covenant in this case does. He said considerations for distinguishing the two include the intent of the people covered by the covenant, it has to equally benefit and burden everyone it covers, and it has to run with the land and bind future owners. He acknowledged the Colorado Supreme Court hasn’t ruled before that an equitable servitude is a property interest.

Joseph Rivera of Murray Dahl Beery & Renaud, representing the Town of Monument, argued a restrictive covenant isn’t enforceable against a local government exercising its eminent domain authority. Colorado law is distinctive because it recognizes damagings, which allow property owners right by a condemned property to get compensation.

“We have this middle path, which is a damaging, that provides compensation [and] relief for property owners that are immediately adjacent to the public improvement,” he said. “So it solves the problem of what to do with those properties adjacent that are immediately adjacent, and solves the problem of how to figure out who is eligible for relief for those who are not immediately adjacent.”

The justices pressed Rivera about how they might create a rule for determining if a local government is required to compensate a property owner for a public improvement near their land. Justice Richard Gabriel said Rivera’s argument didn’t seem to answer how to differentiate between property owners whose land is, say, two lots versus three lots away from the public improvement.

“If you’re six miles away from this sewage plant in my hypothetical, you probably don’t have any damages,” said Gabriel. “Why doesn’t that work: We say it is a property interest, it is a taking; it’s on the burdened owners to prove any damages that they have?”

After several more minutes of questions from Gabriel, Rivera seemed to acknowledge the lot purchased by the town is a property interest. But he said the damages would be limited to that lot and again argued a restrictive covenant doesn’t create a property interest.

But when Hart asked him whether, if Monument had condemned the lot it planned to build the water storage tank on instead of purchasing it, the town would have had to also condemn the restrictive covenant, Rivera said yes.

“That makes it sound like it is a property interest,” Hart said.

Rivera said because the homeowners association knew what the town planned to do with the lot, Monument needed a court order clarifying it had the right to build on the property to avoid the HOA taking legal action to prevent it.

Later in his arguments, Justice William Hood said he wasn’t comfortable making a decision based on the distinction between takings and damagings, because the parties didn’t brief the issue. Rivera added he doesn’t think the court should consider the damages piece of Colorado law, but he brought it up to point out how state law is different from other states.

When the justices pushed Rivera for a definition of property “adjacent” to a public improvement and Rivera said it means “contiguous borders,” they slipped in a reference to another set of property law cases the court is considering about how to differentiate residential land from vacant land for property taxes: Does “contiguous” mean land plots have to physically touch?

“We’ve talked a lot about what does ‘contiguous’ mean,” said Justice Monica Márquez.

— Julia Cardi