Revisions made earlier this month to Colorado Rule of Civil Procedure 16.1 aim to improve access to courts for civil cases.

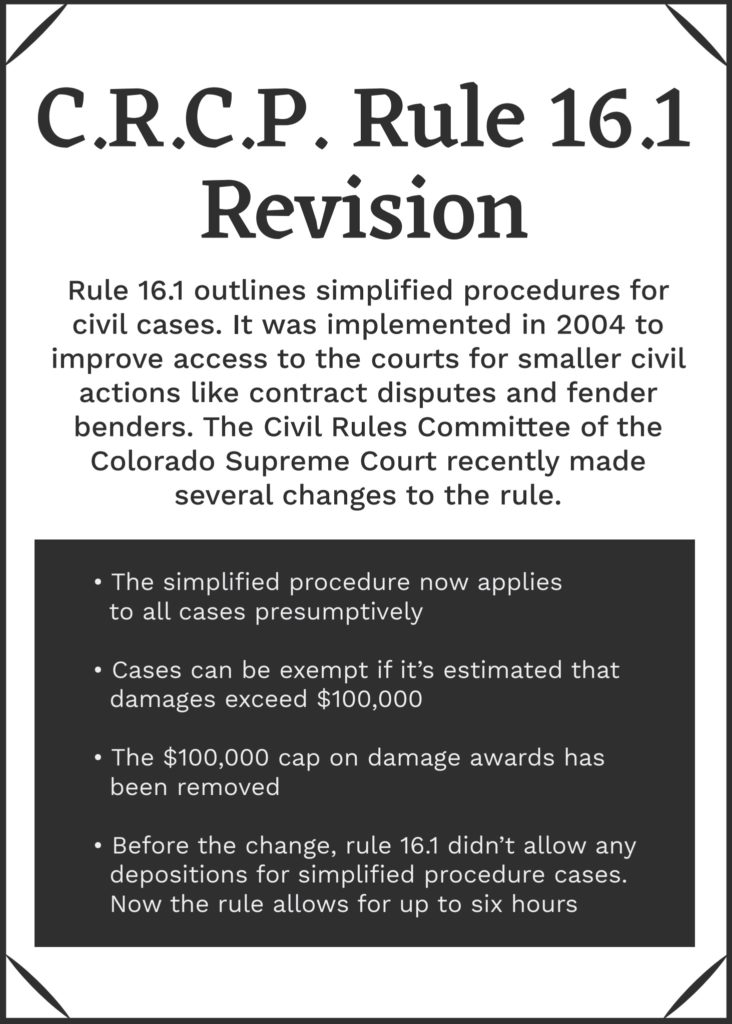

The rule lays out “simplified procedures” for civil actions such as contract disputes and small claims. It implements guidelines to expedite proceedings by limiting discovery and speeding up cases. The recent tweaks to the rule aim to take that process one step further.

The rule was implemented in 2004 in an effort to improve access to justice in civil courts. The rule applies to all civil actions other than cases that carry their own separate courts or special nuances, like class actions, domestic relations, juvenile or water law among others.

During a pilot project for the rule — launched in two courts prior to its wider implementation — a committee considering the rule found that more than 50 percent of cases filed were for damages or claims less than $100,000, said Davis Graham & Stubbs senior counsel Richard Holme. The now-simplified procedure provides a different avenue for cases where damages will exceed the limits of small claims court ($7,500) but aren’t likely to exceed $100,000. Previously, Rule 16.1 had a $100,000 cap on damages, and any verdict in excess of that amount would be reduced to $100,000, but the revision removes the cap. Now, one or both parties must show the case is large enough and will likely substantially exceed $100,000 to be exempt from the rule.

“The concern expressed was a constitutional concern of whether providing a cap on cases in a certain court would somehow be viewed as matter of substance and therefore needing legislative pronouncement, or matter of procedure in which the case court could do it,” Holme said. “The court didn’t want to be saying ‘You can’t get more than $100,000, then someone would complain to the legislature that someone was usurping authority.’”

One of the significant changes to rule 16.1 is in its allowance of depositions. Previously, the rule stipulated that simplified procedure cases were not allowed any depositions. Now, each party is allowed to take up to six hours of depositions. No more than five requests for production of documents is allowed to be served by each party. Holme said he’s had proceedings for $75,000 cases that result in lengthy, and what he sees as sometimes unnecessary, depositions.

“One thing that’s always driven me nuts is that someone can take four or five depositions and ask things like ‘Where did you go to high school? What was your college major?’” Holme said. “Who cares? My reaction is you don’t need all that stuff. Figure it out and learn how to ask questions.”

In 2012, the Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System studied the effectiveness of rule 16.1.

The study found that there were some benefits, but overall, most attorneys and cases were not using the procedure. It found mixed evidence on whether the rule impacts the length of time to resolve cases but did find that in cases where the simplified procedure was used, 37 percent fewer motions were filed, an “indicator of decreased costs both to the litigants and to the court.”

A defense attorney interviewed for the study gave the example of a $500,000 real estate case that required only one deposition and noted there “is a general sense that if the rules allow for 10 depositions, 10 will be taken,” and that in some cases, they are unnecessary.

Holme said the simplified procedure adjustment that limits the amount of discovery helps to speed up and cheapen the process for both parties.

“It gives people in small cases plenty of opportunity to look at witnesses, ask questions and test whether their memory is good, so you can get to the heart of the crucial issue,” he said. “And you find out that in most cases of that size, you can get most of the information you need to get out in that format.”

Holme said insurance companies have been the primary critics of the rule revision and that sometimes they can make cases costlier than needed, especially for smaller claims.

“They’re used to being able to beat up people and persuade them not to file or give up early, and I understand insurance companies have the right not to just throw money at people because they say they’ve been hurt,” he said. “They’re entitled to find out what happens, but you hear story after story where it turns out they didn’t really need that information, but it costs the other side a lot to get it.”

— Kaley LaQuea